Higgins et al. - Towards a Definition of Disentangled Representations

Published:

Disentanglement is a concept rooted in geometric deep learning.

Disentanglement

We made the case for using geometric priors in the AMMI 03 post and argued for their merit for generalization. To see the relationship to modern machine learning methods, we will now focus on disentanglement in representation learning.

Disentangled representations mean, in an intuitive sense, that the latent factors a neural network learns are semantically meaningful.

For example, this implies that for a 3D scene with objects, the latent representation should separately encode size, color, shape, and position. Nonetheless, this is a vague concept: indeed, current methods include a wide range of inductive biases and conjured a diverse range of metrics. Having uncorrelated factors make sense, but is that the whole picture?

For me, disentanglement was this vague concept a lot of people are interested in, but could not express it explicitly. After spending some time to study the essentials of geometric deep learning, I found the notions of invariance, equivariance, and symmetries useful to think about disentanglement. Of course, I was not the first: this post relies on (Higgins et al., 2018) to provide a geometric deep learning perspective of disentanglement.

But first, we should be more specific than saying what we want is semantically meaningful latents.

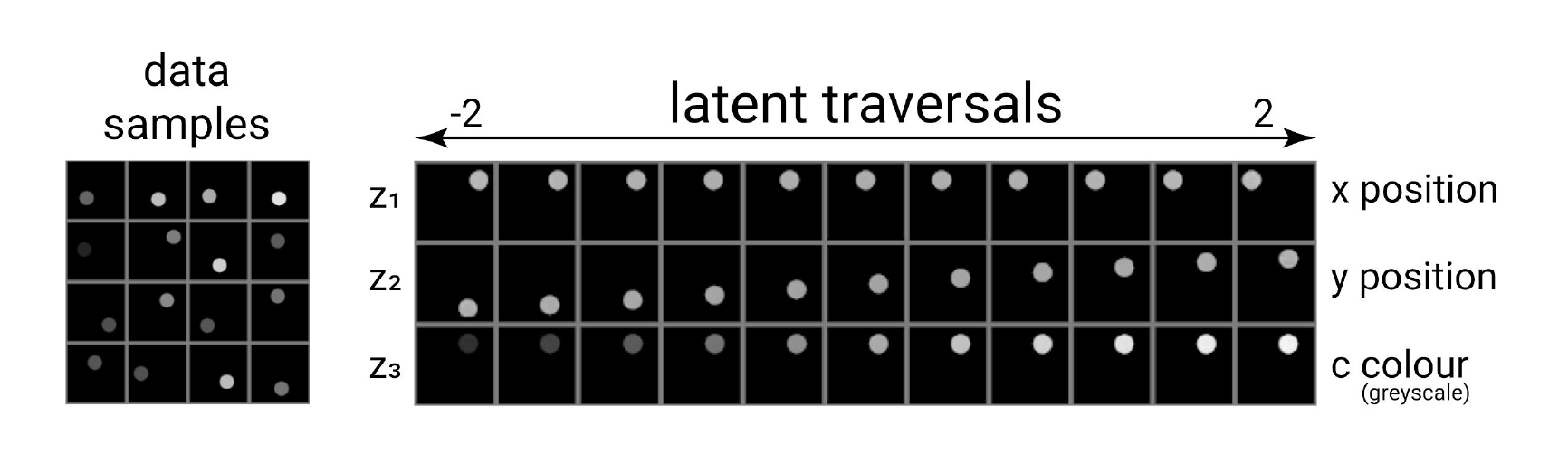

Visually, this is what we expect: for greyscale points on the 2D plane, we want to have $x$-, $y$-position, and color as our latents

What properties should a disentangled representation have?

Our first take is guided by the DCI score, for it quantifies semantically meaningful representations based on how disentangled (modular), complete (compact), and informative (explicit) they are.

Note that disentanglement as a component in the DCI score has an unfortunate name: for a representnation to be disentangled, we require all three components. For this reason, I will use modularity, compactness, and explicitness.

Modular (Disentangled)

Modularity/Disentanglement Modularity measures whether a single latent dimension encodes no more than a single data generative factor.

Example

When changing a latent factor $z_i$ changes only one attribute, e.g., the size of the object, then it is modular.

Counterexample

If changing $z_i$ changes both color and size, then it’s not modular in this sense.

What happens when $z_1, z_2, z_3$ encode the 3D position of the object, but not in the canonical base? Is that still modular? We will return to this point later.

Compact (Complete)

Compactness/Completeness Compactness measures whether each data generative factor is encoded by a single latent dimension

Example

Completeness requires that an attribute should only be changed if a specific $z_i$ changes. For all $z_{j\neq i}$, the attribute (e.g. color) should remain constant.

Counterexample

Completeness reasons about the opposite direction than modularity. Namely, modularity is still fulfilled if both $z_i, z_j$ encodes color, but such a representation is not compact.

Explicit (Informative)

Explicitness/Informativeness Explicitness measures whether the values of all of the data generative factors can be decoded from the representation using a linear transformation.

Fortunately, latents are not rude, so no four-letter words are meant by this kind of explicitness. As (Higgins et al., 2018) argue, this is the strongest requirement, as it addresses two points:

- the disentangled representation should capture all latent factors, and

- this information should be linearly decodable

Example

In a 3D scene of a single object with a specific shape, size, position, and orientation, all of these factors correspond to latent factors such that we can extract all information by applying a linear transformation, i.e., $z_{true} = A z_{learned}$. That is, it can happen that a single $z_{learned,i}$ changes multiple factors, but we can find a matrix $A$ such that we get factors where modularity holds.

Counterexample

Condition 1 is hurt if, e.g., color is not encoded in the latents; while condition 2 is not fulfilled if there is no such matrix $A$ that $z_{true} = A z_{learned}$ holds (e.g., there is a nonlinear mapping to $z_{true}$).

A geometric approach to disentanglement

Let’s start with a refresher from AMMI 03 post about what a symmetry is:

A symmetry of an object is a transformation that leaves certain properties of the object invariant.

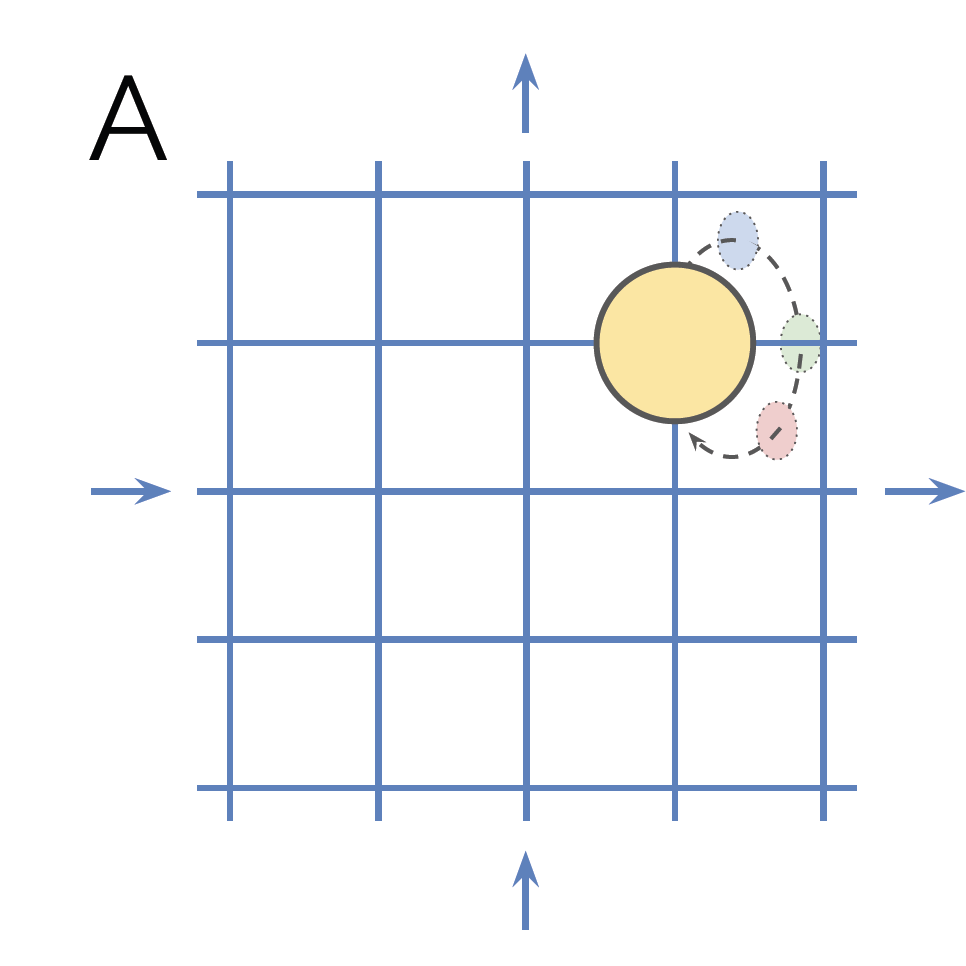

And continue with the same example as in the paper: a grid world with

- a single object,

- four movement directions,

- a single color component (hue), and

- a circular structure (moving off the grid to the right transfers the object the leftmost pixel/the hue spectrum is traversed from its beginning again)

Translation and color change do not change the identity of the object, so they are the symmetries of the example, and as such, they can be thought as a symmetry group $G$. Elements $g\in G$ thus map from data space to data space as $G\times X\to X,$ leading to the conclusion that these transformations are the group actions. Additionally, we can create subgroups from $G$, corresponding to horizontal/vertical translation and color change. To have a disentangled representation, we require that when, e.g., color changes, the position stays the same. Translated to the language of geometric deep learning, this means that a

disentangled group action should decompose into components for each subgroup such that it only affects its corresponding subgroup.

The components are subgroups as they are in $G$ and when we change the corresponding factor (such as color) then we will remain within the subgroup: it does not matter how much we tinker around with color, we cannot get the position to change (throwing a paint bucket at it does not count!).

The first notable point is that here

the disentangled representation is defined in terms of a disentangled group action of symmetry group $G$.

Thus, the disentanglement definition from the paper becomes (it refers to vector representations as the latent space is assumed to be a vector space, i.e., we have latent vectors such that their linear combination is also a valid latent vector):

A vector representation is called a disentangled representation with respect to a particular decomposition of a symmetry group into subgroups, if it decomposes into independent subspaces, where each subspace is affected by the action of a single subgroup, and the actions of all other subgroups leave the subspace unaffected.

This means that the definition depends on the specific decomposition of $G$ into subgroups.

For example, if we define the decomposition with only two subgroups (one for position and one for color), then we do not care about whether the model can disentangle horizontal and vertical position. And this is a very important point.

This definition of disentanglement provides means to fine-tune the granularity w.r.t. which we require disentanglement.

From a practical point of view, this could lead to simpler models as no model capacity needs to be spent to disentangle specific factors. Furthermore, this also means that

There is no requirement on the dimensionality of the disentangled subspace.

That is, even if there is a multidimensional subgroup, e.g., as it comprises of correlated factors, but the corresponding group action only acts on this subspace, then it is disentangled. Such scenarios can arise in the real-world: when encoding both height and age, then they are correlated (there are no two-meter-tall babies).

When this is not enough, we should note that there is

no restriction on the bases of the subgroups.

Thus, position is not required to be described with the Cartesian coordinate axes.

Furthermore, if we impose the linearity constraint on the group actions for all subgroups, we arrive at a linear disentangled representation (this means that we have the matrices $\rho$ from last post’s representation definition):

A vector representation is called a linear disentangled representation with respect to a particular decomposition of a symmetry group into subgroups, if it is a disentangled representation with respect to the same group decomposition, and the actions of all the subgroups on their corresponding subspaces are linear.

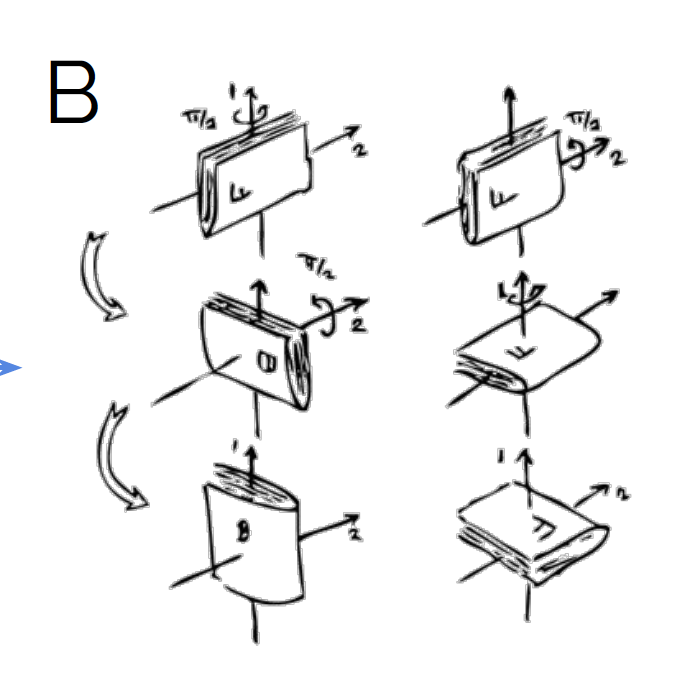

Counterexample: 3D rotations

A somewhat surprising counterexample is the case of 3D rotations. Namely, as they are not commutative (see image below), they cannot be disentangled according to the definition of (Higgins et al., 2018). Namely, the non-commutativity implies that the group actions (rotations around any of the $x$-, $y$-, or $z$-axes) affect the other group actions. Rotating around the $z$-axis means that the rotation around the $x$-axis will have a different effect. Thus, the group actions are not disentangled, and neither is the representation.

Summary

(Higgins et al., 2018) provides a principled definition of disentanglement based on group theory. The main benefit of this is that it enables us to communicate clearly about what we mean with disentangled representations. Furthermore, instead of speaking about “data generative factors” (which is a vague concept), they reason about the well-defined notion of group actions.