Rotating Features For Object Discovery

Published:

Structure is a useful but underleveraged inductive bias for representation learning.

Rotating Features For Object Discovery

I came across the Rotating Features paper (oral at NeurIPS 2023) at the ELLIS Doctoral Symposium in Helsinki. The paper proposes a structured latent space for object-centric learning. In the past months, I have thought about the role of structure in representation learning, and now I am sharing my thoughts.

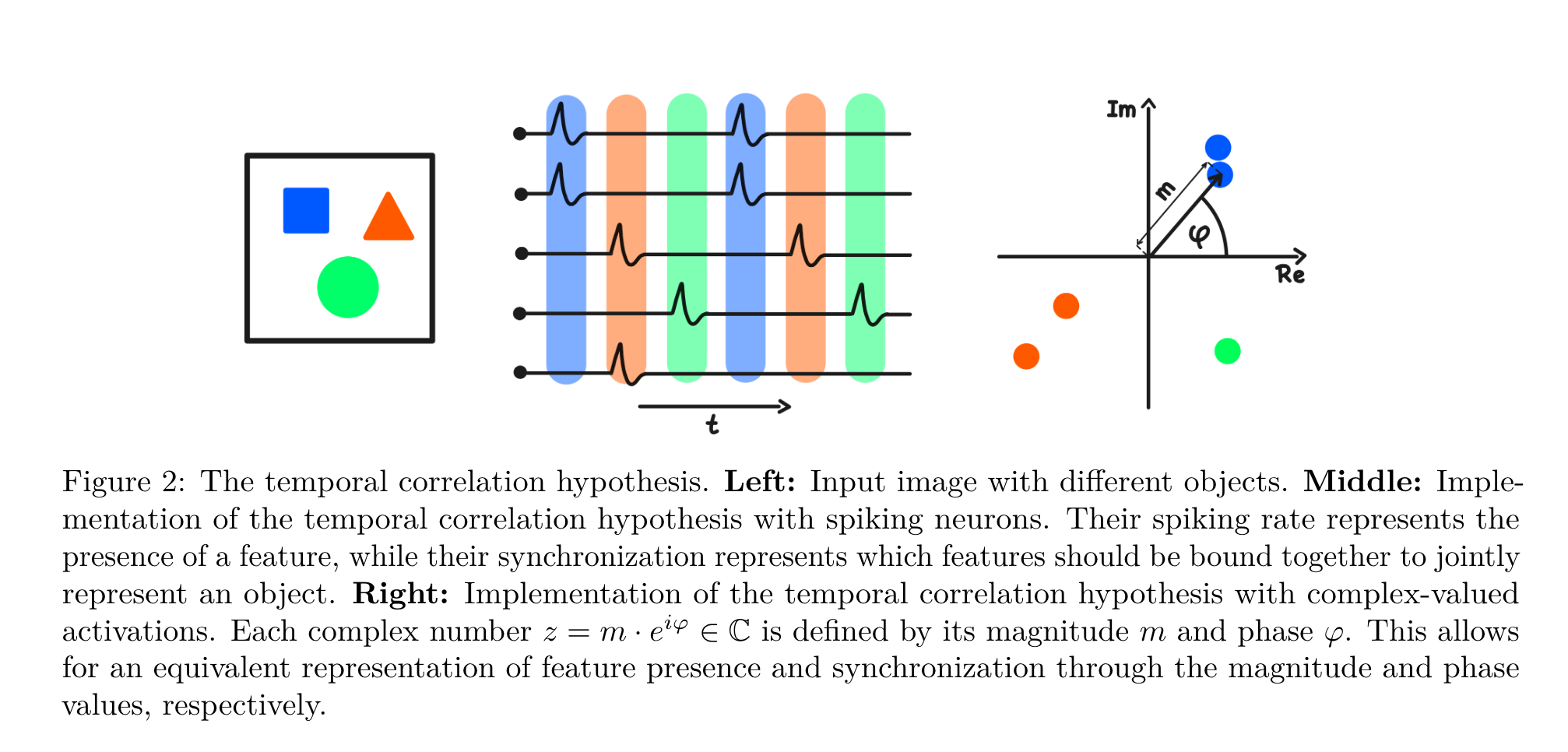

The idea comes from the temporal correlation hypothesis (the figure is from the Complex Autoencoder paper). This posits how neurons modulate their firing frequency and relative timing.

A property’s (latent factor’s) presence modulates firing frequency. High frequency means the property is present.

Different neurons’ fire with a time shift to express the object to which a property belongs. Neurons representing properties of the same object will be firing at (approximately) the same time.

Generally, latent variable models use a scalar for each latent factor. The problem is that a scalar has only a single property: its magnitude. To turn the temporal correlation hypothesis into a representation, we need more. Previous work by the authors suggests using complex numbers, i.e., 2d vectors for each latents. Vectors have magnitude and orientation, so we are done, right?

Not so fast. The Complex Autoenoder (CAE) by the same authors should have done the trick, but it cannot generalize to arbitrarily many objects. E.g., it fails for 10. Intuitively, a problem is that the vectors cannot be spread “very far” on a circle, especially with more objects.

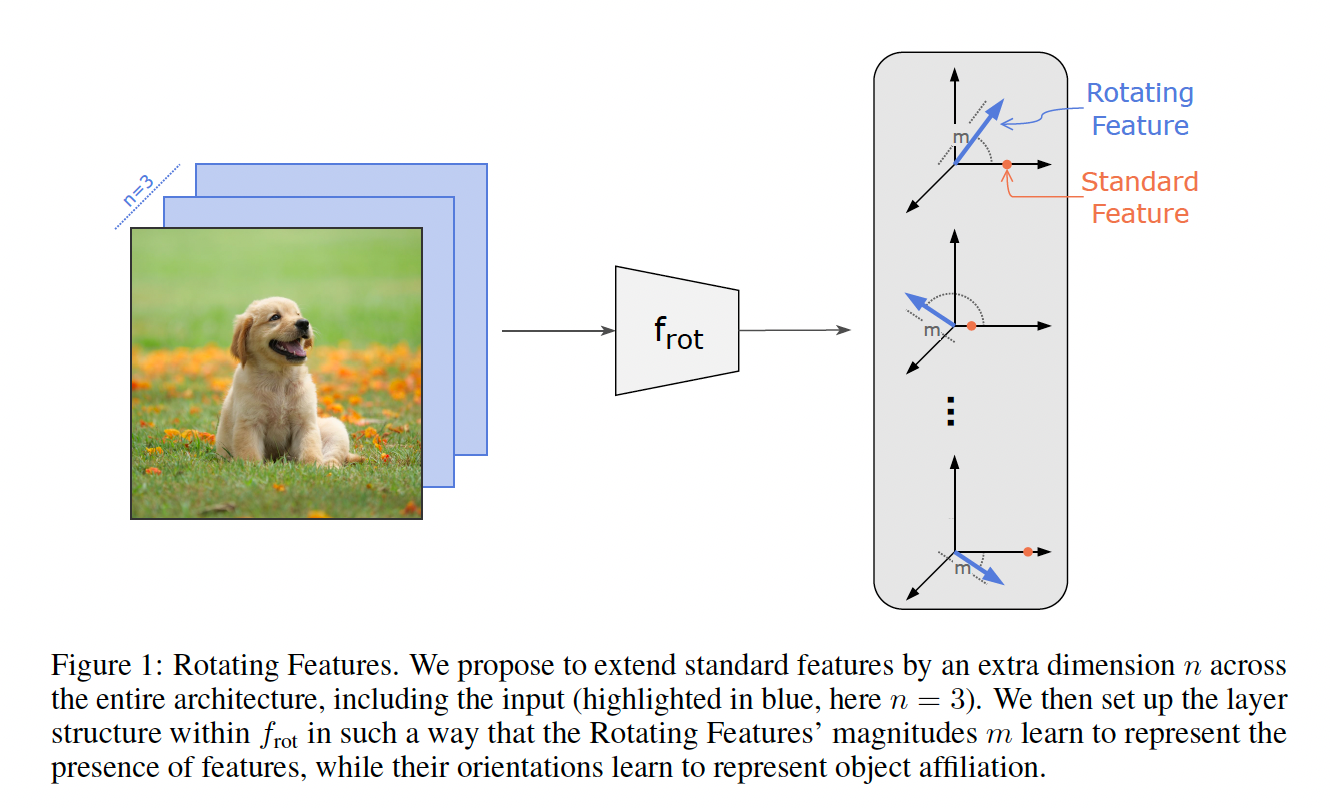

Rotating Features use a hypersphere instead, generalizing the CAE. Intuitively, using a high-dimensional latent space could help on its own. In high dimensions, random vectors with e.g., i.i.d. Gaussian coordinates will be almost surely orthogonal. This means you can spread them out to get distinct clusters for each object’s features. Theoretically, a complex number (as in the CAE) should be sufficient. I suspect that when the vectors are too close (in terms of angular distance), the neural network mistakes them to belong to the same object.

It would be interesting whether performance improves with different inductive biases. Namely, the network uses a so-called binding mechanism that ensures that similar features are processed together. As the authors have shown, the binding mechanism is sensitive to angular distance. That is, it benefits from a higher-dimensional hypersphere, where vectors can be distributed further apart.

Experimental results show clear improvements, but I will focus on the main message:

If you peel back the idea, it comes back to learning a structured representation, where structure is an inductive bias.

And I believe this is quintessential. What most latent variable models models use is an Euclidean latent space. But that fails even on simple data sets like dSprites. WHat causes the problem are discrete (shape) or cyclic (orientation) features. That is, when the topology of the feature does not match the latent space.

You might object that you can represent orientation on the real line in $[0;2\pi)$, and you are right. So you can even have identifiability guarantees. Problems start to come up when you want to measure (angular) distance-see the example in our extended abstract. Suppose you use the real line that comes by default by the Euclidean metric (a.k.a. L2-norm). Well, will that correctly say that an orientation of 0 is closer to $2\pi-\varepsilon$ or $0.1$? Nope!

So you need some structure. Empirical studies have already shown that simply using more components to represent a single latent factor helps. It should not come as a surprise, e.g., consider orientation. You could use an angle $\theta$, or you can use real coordinates (parametrizing a circle, embedded in $\mathbb{R}^{2}$) as $(\cos \theta; \sin \theta)$ . The network may learn to parameterize the circle even without a cosine-sine parametrization. But you cannot do this with a scalar component.

To summarize, Rotating Features relies on a simple idea by introducing structure into the latent space to learn an object-centric representation. I mean it as a compliment: simple is elegant, but not necessarily easy.

Is there a useful structural inductive bias for the problem you want to solve?